Tags

comparative linguistics, historical linguistics, language diversity, languages, linguistics, Swadesh List

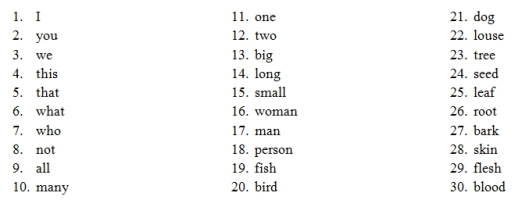

In the 1950s, an American linguist named Morris Swadesh became interested in the rate of change of words within languages. He believed that by calculating this rate of change (which he believed to be constant), one could successfully trace the way languages have evolved over time and in the process demonstrate their relationship to each other. Swadesh set about collecting a sampling of vocabulary items that could be compared cross-linguistically to show change over time. To be effective for his investigations, the items had to be specific, present in all languages, and also equivalent across all languages. So, for example, a word like “computer” wouldn’t be very handy historically, but a word like “mother” would be a good way to compare vocabulary. His list began with 500 words and after many revisions was published as a 100-word list, which has come to be known as the Swadesh List. Here are the first twenty items from the final Swadesh list (the full list can be seen here):

This so-called “universal” list, and its implications, are precise, clear, and neat – which should be your first clue that it is flawed. Languages are fascinating and messy things, so we would be wise to be skeptical that such a broad and clean list could really apply to all languages. There are two key ways to criticize the Swadesh list. One way is to question the way the list has been used in historical linguistics, as a tool for methods called lexicostatistics and glottochronology, methods which were once popular and now largely discredited (I’ll have to write more about that later!)

The other major criticism of the list is its underlying assumption that there exists some set of universal and culture-free vocabulary, common to all languages. Languages do not exist in a vacuum; they are by nature culturally grounded and context-rich. Not only that, but the list assumes that there is a direct, one-to-one match between each vocabulary item in any given language and another individual item in any other language. A simple glance at English versus other European languages shows the flaw in that assumption – whereas modern English only has you for the second person, French has tu and vous, Spanish has tu and usted, Russian has ты and вы. The final draft of the Swadesh list clarifies that the “you” (item 2) on the list is meant to be second-person singular, specifically, but that does not completely solve the problem. Tu in French does not just indicate singularity, but also familiarity and intimacy – you call your brother tu but your professor vous. Therefore, it is not accurate to say that French tu and English you (second person singular) are equivalent and convey the same meaning.

Lyle Campbell gives other examples, such as the fact that Navajo does not have a single stand-alone word for “water” (item 75 – instead they have words for “rain water,” “drinking water,” “stagnant water in a pool,” etc.), and the fact that Finnish does not have a stand-alone word for “not” (item 8). Campbell also notes that many languages do not distinguish a difference between two or more items on the list. For instance, the word for “man” and “person” are the same in some languages; in some indigenous Latin American languages the root of a tree is something like “tree hair,” which makes it hard to argue for one-to-one equivalents for “root” (item 26). [1]

It is interesting to note that it’s not just historical linguists who misunderstand the cultured-ness of languages when they use this list. Dixon notes that some field linguists, eliciting language from a native speaker in order to document the vocabulary of that language, might use the Swadesh list, a technique he notes is “foolish.”[2] Since we know it is foolish to assume every language has a one-to-one equivalent for every item on the list, I can understand why he is dismissive of a fieldworker who ignores the input from the speakers around him in favor of a so-called “universally applicable word list.”

The idea that one word in my language equals another single word in another language is an assumption that linguists and language learners alike have to challenge and move past. While something like the Swadesh list seems handy, in the end the vocabulary of a language can only be defined in the context of that language itself. Attempts at universal equivalencies of meaning fall flat when confronted by the messy, nuanced reality of living tongues.

[1] Campbell, L. (2004). Historical linguistics: an introduction (2nd ed.) Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp. 204-206.

[2] Dixon, R.M.W. (2010). Basic Linguistic Theory. Volume 1 Methodology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 299.

Copyright Allison Taylor-Adams. See About for details.

Pingback: “How languages evolve” on TEDEd | polyglossic