Tags

endangered languages, language diversity, language revitalization, languages, linguistics, Native American

I’m back after two of the most exhausting, exhilarating, challenging, and rewarding weeks I’ve had in quite a long time.

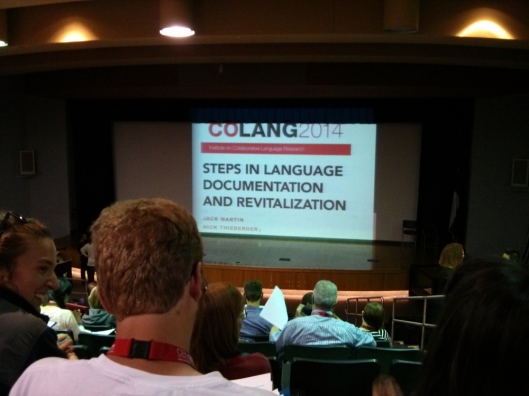

CoLang (i.e. the Institute for Collaborative Language Research) took place at the UT-Arlington, under wide Texas skies.

The participants and instructors came from colleges, universities, indigenous communities, and development organizations. They were from all over the US and Canada, Australia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Mexico, China, Japan, and Iraq (and those were just the people I managed to meet!) I met someone who documents languages on Vanuatu; someone else who has a community development project in Ecuador; someone else is working to document the languages of Zapotec immigrants living in central California; someone else who is developing language programs for her own tribe in Iowa.

The participants and instructors came from colleges, universities, indigenous communities, and development organizations. They were from all over the US and Canada, Australia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Mexico, China, Japan, and Iraq (and those were just the people I managed to meet!) I met someone who documents languages on Vanuatu; someone else who has a community development project in Ecuador; someone else is working to document the languages of Zapotec immigrants living in central California; someone else who is developing language programs for her own tribe in Iowa.

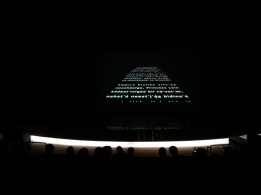

The courses kept us all plenty busy during the day, and every evening there was something to participate in, including sharing nights, public lectures, and of course, Star Wars in Navajo (!)

I had personal triumphs, such as when the instructors of my Audio class listened to a practice recording my partner and I had made and said things such as “wow” and “the quality of this is so good, I would use this.” I had personal struggles, such as time spent desperately searching for something caffeinated, or running out of minutes on my phone plan because I couldn’t stop giving my husband long detailed updates.

On the last day of the institute, several participants who had received scholarships to attend got up to say thank you and to talk about their experiences. They all talked about how important this work of documentation and revitalization is, and how transformative the time at CoLang had been. One undergraduate looked at the auditorium full of people and said, “You all make me proud to be a linguist.”

And that’s what I wanted to say too. Because at the end of all of it, the courses and the training were important, of course; I certainly learned a lot. But the richest part of the whole thing was meeting and making friends with so many kind, interesting, smart, creative, selfless people. You go to this thing and you learn about work being done, and you watch partnerships form, and you find buddies and allies that you might not have ever met otherwise. I feel so honored to have had that opportunity.

Mark your calendars for CoLang 2016 at the University of Alaska Fairbanks! 🙂

Copyright Allison Taylor-Adams. See About for details.